Imagine two continuous random variables seemingly unrelated and free from any influence from each other. It’s a common assumption in probability theory that independence implies a lack of any relationship between variables.

However, a fascinating theorem challenges this notion, showing that from any two independent continuous random variables, we can construct new deterministically dependent variables that not only share the same distributions but also have joint distributions that are arbitrarily close.

In other words, independence can be deceptive, leading us to a realm where variables are closer than we think. Let’s explore this intriguing theorem and its implications.

(If you could link me up with a paper that talks about this theorem, please do. I couldn’t find it. This theorem is apparently proven by “Nelson”. Edit: I found it.)

Theorem

Let \(X,Y\) with \(F_X, F_Y \uparrow,\) be independent continuous random variables on \((\mathbb{R}, \mathcal{B}, P)\). For all \(\epsilon > 0\) there exist deterministically dependent \(U,V\) on the same probability space \(F_U = F_X, F_V = F_Y\) and \(\sup_{(a,b) \in \mathbb{R}^2} |F_{U,V}(a,b) - F_{X,Y}(a,b)| < \epsilon\).

Here is the proof I came up with:

Proof

We can instead work with the random variables \(\frac{1}{1+e^{X}}\), and rename \(Y\) similarly too, to work with random variables bounded in \([0,1]\).

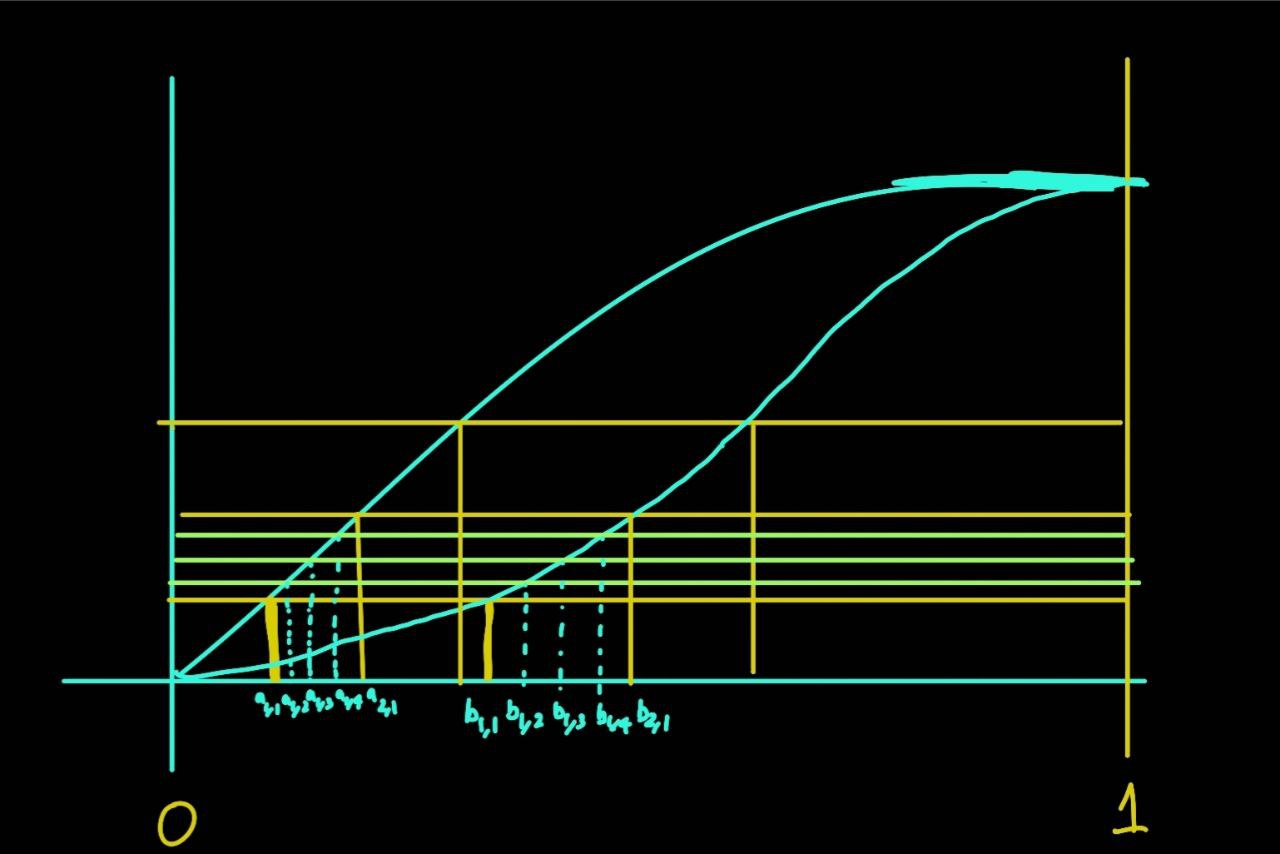

Fix positive integer \(n\), and obtain \(\{a_{0,0}=0 < \cdots < a_{0,n-1} < a_{1,0} < \cdots < a_{1,n-1} < \cdots < a_{n-1,0} < \cdots < a_{n-1,n}=1\}\) and \(\{b_{0,0}=0 < \cdots < b_{0,n-1} < b_{1,0} < \cdots < b_{1,n-1} < \cdots < b_{n-1,0} < \cdots < b_{n-1,n}=1\}\)

such that \[F_X(a_{j,0}) - F_X(a_{j-1, 0}) = \frac{1}{n}, \ F_Y(b_{j,0}) - F_Y(b_{j-1, 0}) = \frac{1}{n}\] \[F_X(a_{j,i}) - F_X(a_{j, i-1}) = \frac{1}{n^2}, \ F_Y(b_{j,i}) - F_Y(b_{j, i-1}) = \frac{1}{n^2}\] \[\implies F_X(a_{i,j}) = F_Y(b_{i,j}) = \frac{i}{n} + \frac{j}{n^2}\]

\[I_{i,j} = \{a_{i, j} \leq x \leq a_{i, j+1}\}, \ J_{j,i} = \{b_{j, i} \leq y \leq b_{j, i+1}\}\] \[I_i = \cup_{j}I_{i,j}, \ J_j = \cup_{i}J_{j,i}\] The idea is to reorder \(X\) in a way such that \[x \in I_{i,j} \iff y \in J_{j,i}\]

Hence we would want something like this \[P\left(X \in \cup_j I_{i,j}\right)\cdot P\left(Y \in \cup_i J_{j,i}\right) = P\left(X \in \cup_{j}I_{i,j} \text{ and } Y \in \cup_{i}J_{j,i}\right) \] \[= P\left(U \in \cup_{j}I_{i,j} \text{ and } V \in \cup_{i}J_{j,i}\right)\]

Let \(V \equiv Y\), we would want to construct a bijective function \(g:[0,1] \to [0,1]\) such that for \(y \in J_{j,i}\)

\[F_Y(y) - F_Y(b_{j,i}) = P\left(b_{j,i} \leq Y \leq y\right) \stackrel{\textcolor{red}{!}}{=} P\left(b_{j,i} \leq g(X) \leq y\right)\] \[\stackrel{\textcolor{red}{!}}{=}P\left(a_{i,j} \leq X \leq g^{-1}(y)\right) = F_X(g^{-1}(y)) - F_X(a_{i,j})\]

\[F_X(g^{-1}(y)) = F_Y(y)+(F_X(a_{i,j}) - F_Y(b_{j,i}))\] \[\stackrel{\textcolor{red}{!}}{=}F_Y(y) + \left((i-j) \cdot \left(\frac{n-1}{n^2}\right)\right)\] \[x = g^{-1}(y) \stackrel{\textcolor{red}{!}}{=} F_X^{-1}\left(F_Y(y) + \left((i-j) \cdot \left(\frac{n-1}{n^2}\right)\right)\right)\]

This is clearly measurable, and it is easy to check that this function indeed satisfies the \(x \in I_{i,j} \iff y \in J_{j,i}\) condition. Take \(U \equiv g^{-1}(Y)\).

I will now be done if I show that \(U\) follows the same CDF as \(X\). For \(x \in I_{i,j}\)

\[P\left(a_{i,j} \leq U \leq x\right)\] \[ = P\left(a_{i,j} \leq F_X^{-1}\left(F_Y(Y) + \left((i-j) \cdot \left(\frac{n-1}{n^2}\right)\right)\right) \leq x\right)\] \[= P\left(F_X(a_{i,j}) \leq F_Y(Y) + \left((i-j) \cdot \left(\frac{n-1}{n^2}\right)\right) \leq F_X(x)\right)\] \[= F_X(x) - F_X(a_{i,j}) = P(a_{i,j} \leq X \leq x)\]

The last equality was legal because \(F_X(a_{i,j}) - (F_X(a_{i,j}) - F_Y(b_{j,i})) = F_Y(b_{j,i}) \geq 0\).

Now as \(n \to \infty\), their joints would get arbitrarily close.

\(\blacksquare\)

(If you would like to use this proof, please email me.)

Using the same idea but fixing things up a little bit for the issues with invertibility, one could also prove the following

Theorem

Let \(X,Y\) be independent continuous random variables on \((\mathbb{R}, \mathcal{B}, P)\). For all \(\epsilon > 0\) there exist deterministically dependent \(U,V\) on the same probability space with \(F_U = F_X, F_V = F_Y\) and \(\sup_{(a,b) \in \mathbb{R}^2} |F_{U,V}(a,b) - F_{X,Y}(a,b)| < \epsilon\).